TIJS Visiting Faculty Member Frank Voigt Collaborates to Produce First English Translation of Walter Benjamin's "Eduard Fuchs, Collector and Historian"

This article is written by Dr. Frank Voigt, DAAD Visiting Lecturer

In the fall of 2015, as a graduate student at the Moses Mendelssohn Center for European-Jewish Studies in Potsdam, I traveled to California. Not primarily to see San Francisco—though I did—but to visit the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University. There, I wanted to examine the exile estate of the German art historian and collector Eduard Fuchs (1870–1940).

In 1933, Walter Benjamin was commissioned to write an article on Fuchs. The commission came from the Institut für Sozialforschung, then recently exiled from Frankfurt to Geneva, and its director Max Horkheimer, editor of the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, where the essay was to be published. Benjamin—already in exile and deeply concerned for his brother Georg, a pediatrician and member of the Communist Party who had been arrested by the Gestapo—accepted the commission. It required substantial study, as he was not yet familiar with Fuchs’s work.

Though trained in law, Eduard Fuchs gained widespread attention with his richly illustrated, multivolume histories of manners, erotic art, and caricature. His Illustrated History of Manners (1909–1912) combined scholarly narrative with an unprecedented visual archive, later reflected in the collection he assembled in his Berlin villa. Politically, Fuchs was an influential, if discreet, figure in the German labor movement and a close friend of Rosa Luxemburg, whom he supported financially during her imprisonment for antiwar activism during WWI. In March 1933, with the Nazi rise to power, Fuchs and his wife Margarete fled Germany via Geneva to Paris—where Benjamin, too, would live in exile and work on several major projects, including The Arcades Project.

Benjamin completed the 40-page essay Eduard Fuchs, Collector and Historian in early 1937. Far more than a tribute, the piece places Fuchs within the social and intellectual history of materialist art criticism. It also serves as a concrete application of Benjamin’s critical method—extracting, as he writes, the critical and productive elements of a work from the standpoint of the Jetztzeit, the now-time: a present shaped by fascism politically, ideologically, and economically.

The Fuchs essay is often misread as preparatory work for Benjamin’s later Theses on the Concept of History, written shortly before his death in 1940. One reason for this is that the essay, before publication in the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, was heavily edited. Horkheimer, who published his own programmatic essay, “Traditional and Critical Theory,” in the same issue was unwilling to present an alternative model of Marxist philosophy alongside his own, which is why Benjamin’s essay was cut substantially, removing over two and a half pages of text and omitting its original structure, which had included ten subheadings. The result was a version that read more like a historical-critical homage than the programmatic materialist critique Benjamin had intended.

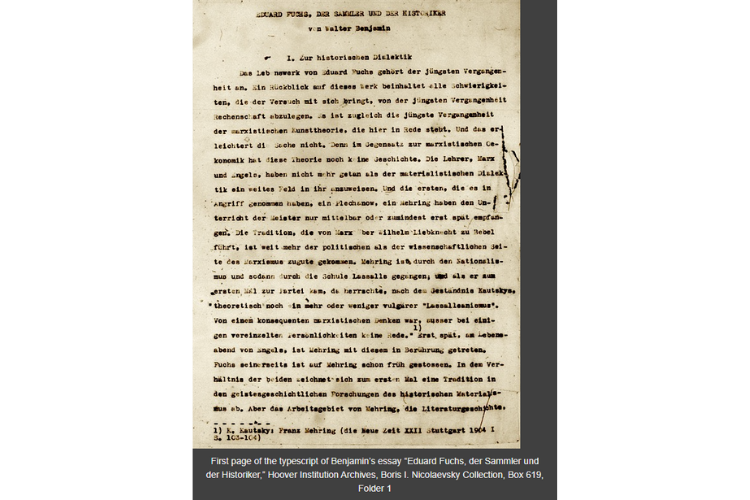

In 2015, while researching the essay for my dissertation, I hoped to locate the original manuscript, which had long been thought to be lost. I could hardly believe my eyes when, in the exile archive of Fuchs at Hoover, I found a carbon copy of the original typescript Benjamin had submitted to Horkheimer. It preserves numerous textual variants and restores the essay’s full argumentative structure and theoretical ambition. The typescript will be published as the final authorial version in Volume 2 of the new Critical Edition of the Works of Walter Benjamin, currently underway with Suhrkamp in Berlin.

Thanks to the generous support of the Tam Institute for Jewish Studies, I will be collaborating with PhD candidate everet smith and Dr. Ben Brewer at the Department of Philosophy to produce the first English translation of Benjamin’s original typescript of the Fuchs essay. Beginning this summer, we will work together to bring this important work into English for the first time, making Benjamin’s full argument—and his complex engagement with Fuchs’s work—accessible to anglophone readers.

Beyond recovering the original scope and nuance of the essay, our translation seeks to reframe Benjamin not only as a theorist of history and aesthetics, but also as a thinker engaged with political practice, the legacy of socialism, and the cultural struggles of his time. At a moment when authoritarian ideologies are again on the rise, revisiting Benjamin’s engagement with Fuchs offers a timely reminder of the urgency of critical, historically grounded thought.

Published 7/29/25